For its entire 124 kilometres, this jewel of a river flows free. It is probably as old as the Western Ghats, older than the Himalayan range. Though not especially long, this west flowing river has a volume of water equal to the bigger Kali or Sharavathi rivers nearby. It originates in Shankara Honda in the town of Sirsi and meanders clean and clear through gorges, unique swamps, ancient forests and agricultural fields, till it flows to the Arabian Sea at Kumta, in Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka. Its forest floors are carpeted by bioluminescence, its estuary is rich with bivalves, crabs and mangroves harbouring dozens of varieties of fish.

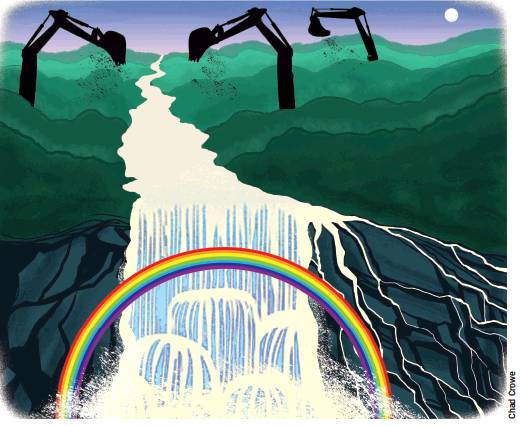

Because of its gradient, it is the site of many spectacular waterfalls, like the Unchalli Falls, near which, on a full moon night in winter, you might even glimpse a moonbow – a rainbow generated from the moonlight. This is the river Aghanashini – ‘the cleanser of sins’.

This peninsular river is unique, because it is free flowing, unpolluted and retains its millennia old natural course. Most rivers in India are not free; they are dammed, or forced into channels. Others have just given up because their catchments have been destroyed; their drainage paths encroached upon. Most of our rivers do not even reach the sea anymore. Yet the hydrological cycle and the monsoon depends on rivers flowing to the ocean. A prevalent hydro schizophrenia refuses to acknowledge this reality, and we continue to build infrastructure along our rivers.

For the lakhs living along its banks, the Aghanashini has given people life and livelihoods. Even today, around two lakh households are directly dependent on the estuary, famed for its protein rich bivalve, crab and shrimp harvest. For the thousands of pilgrims that come to its many sacred spots, the river offers spiritual solace. For the growing number of tourists and researchers, the Aghanashini tract offers unique sights. Its sacred groves where trees have never been felled, its dense mangroves, its endangered lion-tailed macaque that came five million years ago, its tribal populations like the Halakkis that keep the Yakshagana art form alive; its appemidi wild mangoes that make the best pickles; its salt and pest resistant kagga rice – the list is endless.

Periodically, infrastructure is planned along this free flowing river of peninsular India. Once, industrial salt production was tried and abandoned. Then came a hydroelectric project, a thermal power plant, a port and a scheme to divert the river water for faraway towns.

People poured out in strong and sustained protests; people from every walk of life – ecologists, spiritual leaders, and fisher folk. The plans were shelved. The river ran free.

Now, a mega all weather port is once again imagined at its estuary, as part of Sagarmala. This port, which will expand the existing small Tadri port, will be built at an expense of about Rs 40,000 crore.

Karnataka already has 13 ports along its 300 km coastline, out of which one, Mangaluru, is a major port handling the bulk of shipments to and from the state. It is not clear on what basis the state expects Tadri port to be viable when nearby ports remain underutilised.

Just 25 km north is the Belekeri port, which was used to export iron ore and import coal before the industry collapsed. Just 25 km south is the Honnavar port, with a recorded maritime history going back centuries. Both these are well connected through the Konkan railway line and NH-17.

While it is unclear whether this port will ever be economically viable, environmental clearances have speeded up, with the usual contestations over what the reports left out in terms of the natural wealth of the region, and what would be lost through the creation of this port.

Meanwhile, the economic and future proofing opportunities created by the river and its catchments have not been properly documented. With its extreme natural beauty, just the potential of eco-tourism, if properly handled, could yield substantial revenue. The Western Ghats together with the sand and mangroves at the estuary are also effective carbon sinks. They provide untold ecosystem services in the region, including flood and erosion prevention.

If the port is built, it will require extensive dredging, as the current water depth is hardly two metres at the estuary. For ships to dock, it will have to be dredged up to almost 20 metres, releasing a vast amount of carbon rich soil and sand. Who will benefit? We often destroy ecology-based livelihoods in the name of employment creation. Who will be accountable when the marine production drops, as has been the experience at ports close by?

Economic discipline requires an ecological discipline as well. If we go ahead with each and every port designed for the Sagarmala project, we may create stranded assets and waste billions of dollars in underutilised infrastructure. Exactly the same result is visible in the Himalayas where dam after dam was built without making a holistic, scientific assessment of the total impact on the land and the economy.

In this great nation of saints and poets, public administrators and ingenious architects, has our national and local imagination shrunk so much that we cannot leave the last major free flowing river of peninsular India alone, for future generations to explore, enjoy and benefit from? Let the Aghanashini flow with Aviral, Nirmal Dhara.

Source: Times of India, 10 May 2019, Chennai.