The 2000-year-old Samanar Malai, popularly known as the Jain Hills, has a lot of insight to offer on the history of Madurai and its Jain roots. But localities rue that the site has not been promoted well enough for tourists to mark it a must-visit in their itinerary. Forget placing signboards to direct people to the place, they say that the Samanar Malai, despite being taken over by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), lacks even the basic information boards that describe its history and significance.

Bala Krishnan, who’s pursuing his B Ed in Thiyagaraja College, says, “Leave alone tourists, even people from Madurai don’t know much about this site.”

Rewind to the Past

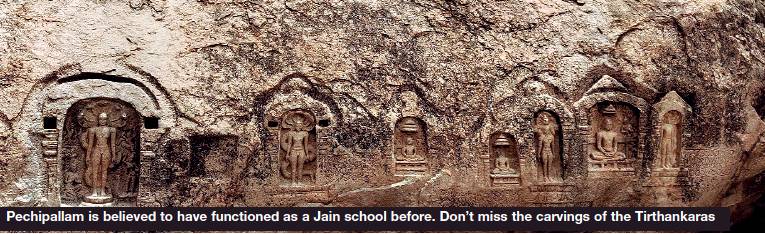

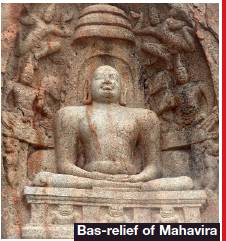

An alluring lotus pond welcomes you as you reach the foothills of Samanar Malai, which is just 15 km away from Madurai. And then, there are two important sites on either sides of the hill. The one at a slightly lower altitude on the left of the entrance is called Pettipodavu, and it houses one of the biggest bas-reliefs of Vardhamana Mahavira in south India that dates back to 5th century AD, along with four more carvings. It also has inscriptions in Brahmi script and Vattaeluthu scripts (literally translated to rounded alphabets), which dates back to 5th and 9th century AD. The other site, called Pechipallam, is accessible through stairs from near the Karuppanaswamy temple. It has nine carvings, including those of Jain Tirthankaras and Gomateshwara or Bahubali (son of Mahaveera); unfortunately, one of them was vandalised 30 years ago. Though this one’s at a higher altitude than the former, both are easily climbable in less than an hour.

A Viable Tourist Attraction

Though not far from the temple town of Madurai, Samanar Hills doesn’t register a huge number of tourist influx. Natives of Keelakuyilkudi, where the site is located, tell us that it is mostly deserted on weekdays and it’s only on weekends that people flock to the place. In the recent past, schools have also started bringing kids here to teach them about the history of Madurai.

While increasing the footfalls is one thing, another issue that plagues this hill complex is cleanliness. Bala Krishnan tells us, “The place is clean at the foothills, but as you climb up, you can find many alcohol bottles and food waste thrown around the site. The place should be maintained with utmost care as it has a huge historical significance.”

The site sustains partly because of the efforts of Keelakuyilkudi natives, who make it a point to sweep and clean up the place every time — almost once a week they come up to pray at the Karuppanaswamy temple. Muthu Pandian, a sexagenarian and native of Keelakuyilkudi, says, “But we do have a tough time controlling vandals. Youngsters from nearby villages sell the steel handrails that were laid out to help tourists climb the hill. Acts like this show the kind of awareness people have about the site.”

Need Government Intervention to Protect the Site

Though a protected monument, locals say that the Samanar Hills complex has not been maintained well and its tourism potential not fully exploited. C Santhalingam, a retired archaeologist and secretary of Pandyanadu Centre for Historical Research, says, “We’ve requested the ASI several times to place a board to educate people about its history, but to no avail.”

Muthu Pandian adds, “The government has to allocate funds every year to maintain this site because it is even older than the Madurai Meenakshi Amman Temple. The archaeological department can levy an entrance fee because there are no other means of revenue to help sustain this historical site.”

What’s in a name?

The Samanar Hills was first called Ammanam Karadi Hills. ‘Ammanam' means nude in Tamil and it was used to refer to the Jain monks who would remain unclothed as part of their code. The word ‘Karadi’ has a mythical connect, and referred to a popular tale in the 20th century, where a bear was believed to have carried water to the top of the hill, where the villagers performed rituals. In fact, one can see a statue depicting this scene at the Karuppanaswamy temple.

Source: The Times of India. 29 June 2019, Chennai.